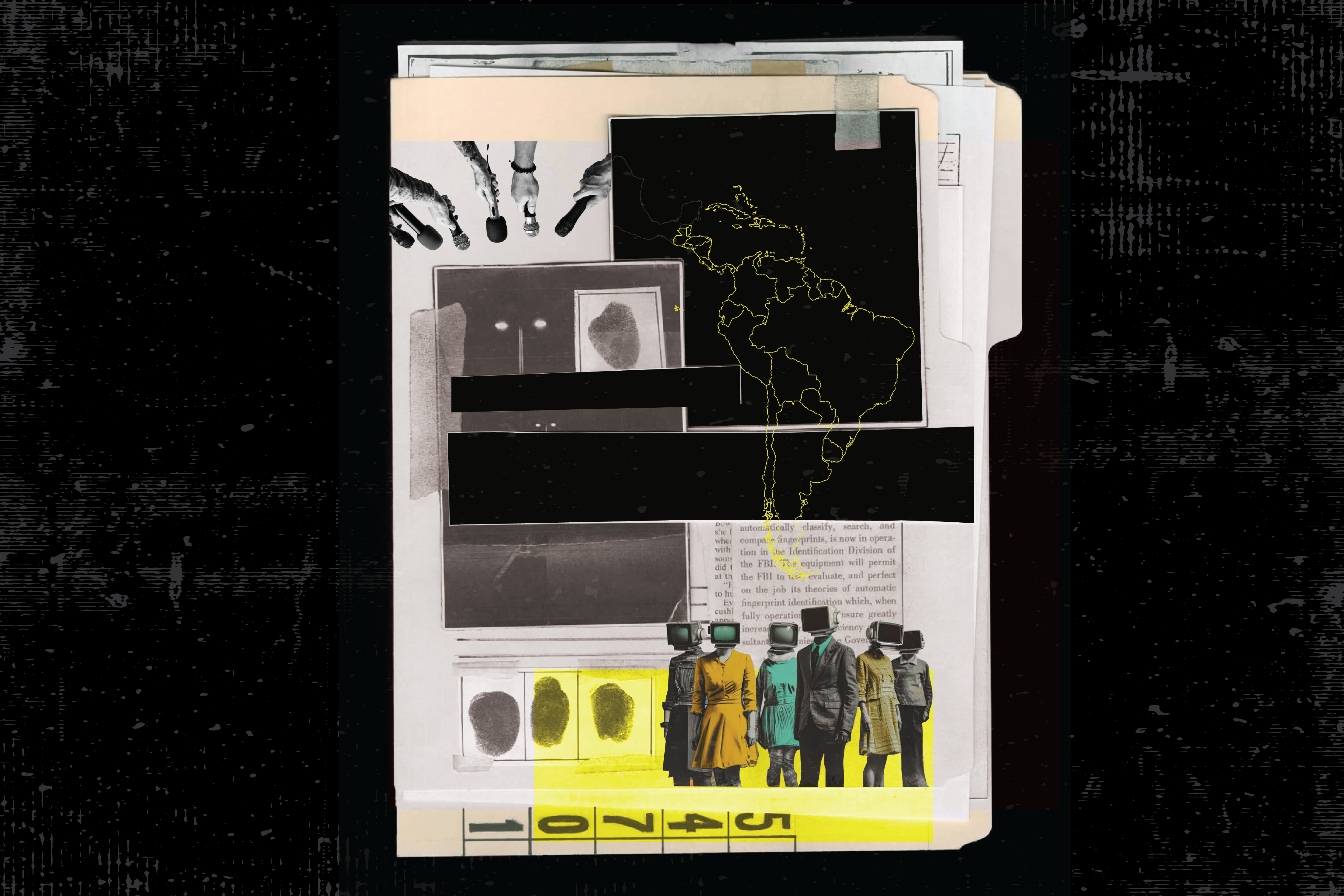

Personal Data Protection in Civil Society Organizations in the Global South: Urgency, Challenges, and Responsibility

In recent years, the importance of personal data has grown exponentially. What was once considered administrative information—names, phone numbers, addresses—is now a strategic asset that influences public policy decisions, state surveillance mechanisms, and the commercial strategies of large technology corporations. For civil society organizations (CSOs), especially in contexts marked by high levels of violence, discrimination, and state or corporate surveillance, the handling of personal data is not a secondary technical matter: it is a question of life, security, and the defense of human rights.

At CAD, we have repeatedly encountered a reality that is both systematic and deeply concerning: many CSOs in Ecuador, Latin America, and the Global South lack solid protocols for the handling, storage, and transmission of personal data, both of their staff and of the communities they work with. This shortcoming is the result of an environment in which funding priorities, technical capacities, and regulatory requirements have not yet pushed data protection to the center of the agenda.

CSOs work with vulnerable populations: human rights defenders, Indigenous communities, survivors of gender-based violence, migrants, environmental activists, and LGBTIQ+ groups, among others. These groups not only face structural discrimination; they are often on the radar of authoritarian governments, security forces, extractive companies, and organized crime networks. Poor handling of personal data (lists of beneficiaries, physical locations, service histories, sensitive images and testimonies, among others) directly exposes these individuals to real risks.

In Ecuador, for example, most organizations do not have clear data classification policies, encryption mechanisms, access controls, or processes to respond to security breaches. Data are often stored on personal devices, email accounts without two-factor authentication, or storage services used without prior risk assessments. These practices, carried out without defined protocols, may seem efficient in the short term but create critical vulnerabilities when unauthorized access attempts occur or when devices are lost.

The risks to which personal data held by CSOs are exposed are multiple and intersect in various ways:

In Ecuador and other countries in the region, there are precedents of surveillance tools being used to monitor human rights defenders or dissidents. The lack of protocols to protect sensitive data increases the likelihood that strategic information will fall into the hands of intelligence agencies or security forces, especially when it involves documentation of human rights violations or accountability processes.

Likewise, large technology platforms and corporations increasingly seek access to databases in order to monetize them or to build commercial profiles. CSOs that use commercial messaging, storage, and project management tools often do so without reviewing terms of service or privacy policies, facilitating data transfers that are not always evident to their teams or beneficiaries.

In addition, in contexts where criminal groups have territorial presence, access to lists of individuals, locations of community centers, or patterns of service provision can become material for extortion, threats, or direct violence. The absence of basic information security measures—such as strong authentication, secure backups, and staff training—amplifies these risks.

In theory, data protection in Ecuador is supported by the Constitution, the Organic Law on Personal Data Protection (LOPDP), and the case law of the Ombudsman’s Office. However, effective implementation of these standards by CSOs is still incipient. The law recognizes rights such as access, rectification, cancellation, and objection, but few organizations have operational mechanisms in place to guarantee them internally.

Across Latin America more broadly, the situation is similar: there are various legal frameworks (for example, Argentina’s Personal Data Protection Law, Brazil’s LGPD, and Chile’s draft legislation), but civil society organizations are often not part of these legal and technical discussions.

Many CSOs operate with limited budgets and prioritize operational expenses, field activities, minimum salaries, and basic infrastructure, leaving aside investments in information security or specialized training.

Moreover, most lack staff with knowledge in cybersecurity, data protection, or digital risk management. This leads to improvised practices, often based on free tools, without prior risk assessments or internal policies.

There is a perception—worryingly common among smaller or community-based groups—that “our data are of no interest to anyone.” This belief ignores the reality that data from vulnerable populations are extremely valuable and sensitive, not only to criminal or state actors, but also to digital intermediaries that trade in them without transparency.

Unlike private companies that face regulatory audits and sanctions for noncompliance, CSOs are not always subject to systematic scrutiny regarding how they handle personal data. This reduces the pressure to formalize processes, even when regulations and institutions for data protection already exist.

Personal data protection in civil society organizations should be understood not as a bureaucratic barrier, but as an extension of their ethical commitment to the communities they serve. This means recognizing that every data point represents a person, and that the impacts of a data breach can be as harmful as a physical attack.

Some key practices that every organization should consider include:

- Developing clear internal policies: This includes defining what data are collected, why, how they are stored, who has access to them, and how long they are retained. These policies should be documented and accessible to the entire team.

- Ongoing training: The weakest link in any security system is the human factor. Training teams in good practices—such as recognizing phishing attempts, using strong passwords, and managing access permissions—can dramatically reduce risks.

- Encryption and access controls: It is not enough to have data; they must be protected. Using tools that encrypt information in transit and at rest, as well as multi-factor authentication to access systems, are essential measures.

- Periodic risk assessments: Identifying critical points—such as storage in third-party services, unprotected mobile devices, or uncontrolled physical records—helps prioritize investments and mitigation strategies.

- Transparency with communities: Informing beneficiaries about how their data will be used, what rights they have, and how they can exercise them strengthens trust and reinforces a rights-based approach in everyday work.

In Latin America and the Global South, where states fluctuate between authoritarian practices and limited institutional capacity, CSOs cannot and should not face the complexity of protecting sensitive data alone. Cross-sector solidarity—among human rights organizations, academics, digital activists, and legal advocates—is not only useful, but indispensable.

It is vital to recognize that protecting personal data is not merely a technical issue; it is a political and ethical stance. For civil society organizations, this means affirming that digital rights are an integral part of human rights. It means acknowledging that in a hyperconnected world, the security and dignity of those who entrust their information to our organizations depend on our ability to manage it with responsibility, transparency, and ethics.

If our policies, practices, and technologies do not evolve to respond to the risks of our time, we run the danger of reproducing in the digital space the same relationships of harm and vulnerability that we seek to change offline. That is why investing in data protection is not a technical luxury: it is an act of defense of life, freedom, and justice.